About K.P. Ambroziak:

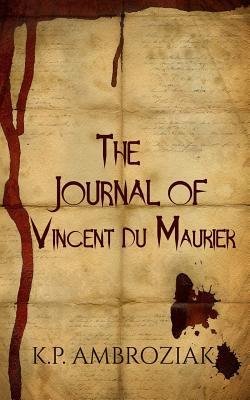

You can purchase her works: THE JOURNAL OF VINCENT DU MAURIER BOOK I, THE JOURNAL OF VINCENT DU MAURIER BOOK II, A PERPETUAL MIMICRY, THE TRINITY, EL & ONINE, and "The Piano String."

You can find her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and Amazon.

Guest Post:

Dark fantasy has got me thinking about my soul. Not in the spiritual sense, or the metaphysical, or even the poetic. But in the aesthetic sense. Let me see if I can make sense of what I mean. We all know the saying, the eyes are the window to the soul, and perhaps some may even know the biblical adage: “The eye is the lamp of the body” (Matt 6.22). Either way you spin it, the turn of phrase is poetic to be sure. But what if the reverse were true? What if we have it backwards, and the soul actually captains the eyes, directing them to see? Alters the idea of “seeing,” doesn’t it?

Dark fantasy, horror, the sublime, the fantastic, and the creepy challenge our ways of seeing and essentially our soul. But from where do these strange tales come? We can certainly find demons haunting the literary landscape well before the first gothic novel. Antiquity is filled with dark figures, manipulating man’s sight for their own means; and Dante’s pit of Hell is abundant with perverse and perverted embodiments and bodies blinded to present-day happenings as punishment for polluting their souls; and we could ask Doctor Faustus. He’d tell us a thing or two about losing one’s soul. Once he’d sold his, he lost all perspective, wallowing in a vat of empty knowledge and blind amusement playing parlor tricks with Mephistopheles until the devils came for payment, to flay and tear his flesh to pieces … But I’m getting off track. I wanted to talk about our ways of seeing and how they are so inevitably tied to the soul.

Literature, like the visual and plastic arts, demands we see what is before us and make sense of what we see. Literature that finds itself on the darker side makes greater demands on us, expecting us not only to see, but also to illuminate what we see. Seeing, in fact, has always been a part of gothic fiction. Take Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN as example – that poor creature, monster that he is, was terrorized by how others saw him. Until the De Lacey siblings had discovered him, papa De Lacey, blind to the horror in front of him, was content to converse with such a gracious and compassionate guest. We as readers can readily sympathize with the creature because we do not have to look at him, but need only imagine his abhorrent figure, which is not the same as witnessing it with our eyes, our soul. Anyone who doubts Mary Shelley challenges our ways of seeing hasn’t read the same text as me (which is very well a possibility, but that’s a whole 'nother post).

Shelley works with sight but also the sublime, a mere by-product of her luscious prose and the time in which she wrote (hanging out with poets like Percy and Byron couldn’t have hurt, either). Frankenstein is evocative of, and reliant on, the terrifying landscape in which its characters live—it is Nature, with a capital N. For her the grandeur of the Swiss Alps and the mystery of the glaciers up North satisfy, but we know even greater majesties of fear—we ride in airplanes and rockets. Can you imagine how mad Victor would think our science? We understand the sublime viscerally, though we may not know it. The sublime is about seeing, and yet it’s also about feeling fear upon that sight. Standing on a precipice, looking over the edge, into an abyss, that’s sublime; walking into a room we know is haunted … wait, I digress again, but surely it’s my prerogative to do so, no?

There’s a faculty bathroom in the college where I teach I’m certain is haunted. I feel it every time I go in there and yet it thrills me to test the eeriness of the atmosphere. I’m always alone in there, despite its row of stalls, and it’s locked, so anyone who enters needs to use a key. But I swear each time I unlock it and walk in the lights flicker just a little and when I see the black garbage bag that’s been wrapped on one of the sinks for repair—every time—I hesitate. It’s like a shadow in the corner of my eye I know is there but don’t want to see. When I see it for what it is I’m still put-off by it, despite its being an ordinary black garbage bag. And then there’s the sound the room makes, the low hum that seems to come from somewhere far beyond the vents, some place like the bowels of a nineteenth century madhouse … But hold on, this isn’t a unique experience. I used to live in The Dakota on the upper West Side of Manhattan. You know the building in which "Rosemary’s Baby" was filmed? Yes, that one. I lived alone in the maid’s quarters on the empty and desolate eighth floor, but my only bathroom was a floor up, and even more desolate, and was the size of a summer camp latrine. Spooky stuff, I tell you, especially since I’m one to drink a cup of tea before bedtime …

Okay, back to the sublime—sight and soul. I’d say it was the Romantic poets who really got the sublime, the terror and darkness of grandeur. For Longinus, the sublime was great and lofty rhetoric, grand thoughts; and the kind of sublime Kant refers to is that which enlists tall oaks and lonely shadows rather than flower beds and low hedges; night is sublime, day is beautiful; the sublime moves and the beautiful charms. But it’s Burke who says it best: “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime ... terror is in all cases whatsoever, either more openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.” When I think of terror I immediately think of sight, what I see (or don’t see, perhaps an even more frightening scenario), whether it is bathed in darkness or blown out with light, temporary blindness and visual disorientation stimulate the imagination.

Back to the Romantics who as it goes adopted Milton’s Satan and made him their son, their poetic hero and inheritance, the discarded and unforgivable wretch who warred on his maker. Did you ever wonder how we came up with the Byronic hero? The lonely and sublime figure walking on life’s precipice? Lord Byron, in fact, made no small contribution to dark fantasy. He’s rumored to have penned "The Vampyre: A Tale" (1819), a short story about a bloodsucker who drains the life from everyone he encounters. But we shouldn’t disregard Polidori, who may very well have written it as fan fiction to Byron’s "Fragment of a Novel." And then there’s Lermontov’s “The Demon,” a poem also inspired by the great Lord Byron … Again, I digress, but Byron’s poetry is dark in ways we may not have seen before:

Her eye (I’m very fond of handsome eyes)

Was large and dark, suppressing half its fire

Until she spoke, then through its soft disguise

Flash’d an expression more of pride than ire,

And love than either; and there would arise,

A something in them which was not desire,

But would have been, perhaps, but for the soul,

Which struggled through and chasten’d down the whole.

What is that “something” that arises in those dark eyes, the thing the soul chokes before it escapes? Pity or fear? Horror? The sublime?

We are haunted not only by what we see, but how we see, if we see. When frightened, we say, “did you see that?” Apparitions are things we build out of thin air; they just magically appear, forged in the shadowy corners of our imagination. The noun “apparition” first appears in 1500, used as “unclosing” in reference to Heaven, and to epiphany, as in the Epiphany, when the Christ child is revealed to the Magi. It comes from late Latin, referring to “an appearance” or “attendants” and is first recorded in 1600 as meaning a ghost. Appearance versus apparition; the one is expected, the other startles us. The haunting of an apparition seems to have its roots in antiquity, as poor Narcissus is tortured by the apparition of the one he sees in the lake. He does not know it is his own reflection, cursed as he is, but its disappearance haunts him more terribly than its appearance.

Dark fantasy deals in haunted sightings, and one writer who has mastered this is E. T. A. Hoffman, whose “The Sandman” (1816) is all about “the eyes! the eyes!” as Mister Coppola calls out to potential buyers of his lenses. Coppo is Italian for eye-socket and Klara, of course, symbolizes clarity. “Things are as we see them,” has never rung more true as it does in this short story, for even the reader can’t tell if Nathanael is mad, or imagining the memory of Coppelius, or Coppella. The eyes are of importance here, for they determine how we see, what we see and what our eyes appear to be. How much more may be said of the soul? And then there’s Guy de Maupassant’s “Le Horla” (1887), a particular favorite of mine. The story entails a psychological splitting of the self embodied in the spirit, or, as some say, madness. The narrator is haunted by a passing vessel out in the harbor, and the feeling that arises from seeing it. He is more frightened, in fact, by the invisible spirit since he can’t tell when it will appear. And, of course, Maupassant can’t help tipping his hat to vampirism when his narrator doesn’t see his reflection in the mirror.

But Poe so beautifully questions sight in "The Oval Portrait” I’d be remiss not to bring it up. If you haven’t read this short masterpiece, you must—you really must! I won’t spoil it for you but I think it could be a thesis for my current ramblings: There is an art to seeing, and seeing is an art; dark fantasy encapsulates both most readily.

So dark fantasy takes me to visual art because, well, quite frankly, I think painters and writers are kinfolk. Just as the painter asks his viewer to see his canvas, so too does the writer appeal to her reader’s sense of sight—only her paints are language and her canvas unlimited. But how again do we get to the soul? If you’ve ever seen a painting that has taken you out of the space in which you stood, sucked you into its landscape, or forced you to look, “to see!” by the very strength of its design, you’ve met your soul. It’s the thing that’s forced your eyes to feast on the visual offering, to sacrifice your common sense to the imaginative caves of the mind, to spill blood on the page so you may pass the feeling along to a reader—any reader, willing to swim in the depths of your darkness.

Now, having overstayed my welcome, I leave you with a few lines from Phoebe Cary’s “Dove’s Eyes” to ingest as you see fit,

There are eyes half defiant,

Half meek and compliant;

Black eyes, with wondrous, witching charm

To bring us good or to work us harm.

About THE JOURNAL OF VICENT DU MAURIER:

In the days of the bloodless, a healthy human is a vampire's most valuable resource. But they're in short supply and Vincent Du Maurier is hungry.

Evie could be the last human being alive--and she's pregnant--which makes her situation most inconvenient for Vincent. As he struggles to keep her and her unborn child from both the jaws of the bloodless and the fangs of his starving clan, he faces the most difficult choice of his long life.

If he gives in to his gnawing hunger, he risks a destiny worse than that of the shades in Hades. But if he denies his nature, he could end up turning into something far worse--a vampire with humanity.

No comments:

Post a Comment